Nature mirrored in our bodies

1. Introduction

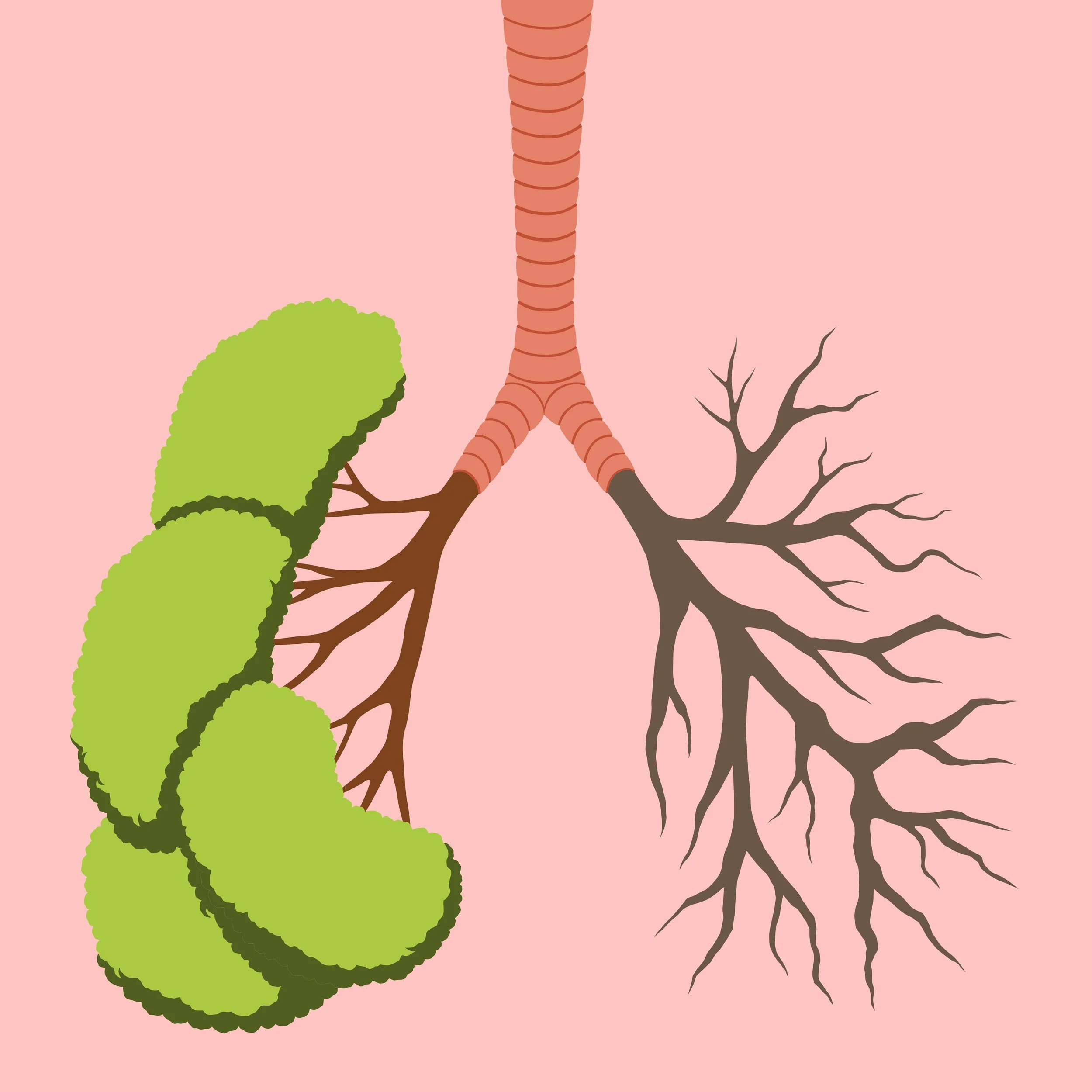

When we pause to observe nature, we often find striking parallels between the natural world and our own bodies. It’s almost as if nature has written its wisdom into both ecosystems and human anatomy, showing us that we are deeply connected to the world around us. One beautiful mirroring lies in the relationship between our lungs and nervous system and the way tree roots and mycelium network beneath the earth.

These systems share striking similarities: they are both intricate webs of connection, designed to sustain life, communicate, and maintain balance. What can this parallel teach us about our bodies, our health, and the environment?

2. The Lungs and Nervous System

Our lungs are a brilliant design. They branch out into smaller and smaller passageways, culminating in tiny alveoli, which are the sites of oxygen exchange. This system is more than just a mechanism for breathing; it’s a vast network that nourishes every cell in the body.

The nervous system mirrors this networked design. With its brain, plexuses, and nucleuses as the command centres and peripheral nerves spreading through the body like an electric web, it transmits messages at incredible speed to keep us functioning. This system is deeply intertwined with the lungs—not just physically but functionally. For example, the vagus nerve, a major component of the parasympathetic nervous system, plays a crucial role in regulating breath, heart rate, and even digestion.

Together, these systems embody connection and flow, constantly adapting to keep us alive and well.

3. Tree Roots and Mycelium

Beneath the soil lies a hidden world that’s as intricate as any human system. Tree roots stretch far and wide to anchor themselves and gather nutrients, and in doing so, they form partnerships with mycelium—the thread-like structures of fungi that weave an underground network.

Mycelium is often referred to as the "Wood Wide Web" because it acts as a communication system for forests. It allows trees to share resources, warn each other of threats, and support one another in times of need. For example, a mother tree can send nutrients to younger trees through this fungal network, much like a parent or caregiver nurtures their child.

Just as tree roots depend on mycelium to thrive, mycelium depends on the roots for energy from photosynthesis. This mutualistic relationship creates balance, fosters resilience, and ensures the survival of the ecosystem.

4. Drawing the Parallel

The similarities between these systems are striking.

Structure: Both lungs and tree roots branch out in fractal patterns, maximising surface area to ensure the efficient exchange of vital resources—oxygen and carbon dioxide in the lungs, water and nutrients in the soil.

Communication: Mycelium transmits messages through biochemical signals, much like how neurons relay information via electrical impulses in the nervous system. Both systems create a web of connection that supports the whole.

Interdependence: Just as a healthy forest depends on its underground network, our bodies rely on the harmony between the lungs and the nervous system. A disruption in either can lead to imbalance and dysfunction.

These parallels invite us to see our bodies as ecosystems in their own right, emphasising the importance of care and balance.

The similarities between these systems deepen when we consider the ecosystems they support—both within us and in the natural world.

Inside our bodies, a vast internal ecosystem thrives, comprising trillions of cells, microbes, and the intricate networks of the nervous and respiratory systems. This ecosystem is not static; it is dynamic and alive, in constant exchange with the energy and signals from the world around us. Every breath we take fuels our cells, but it also connects us to a greater rhythm shared by all living things.

Much like trees in a forest, which communicate and share resources through mycelium, humans are not isolated beings. Our nervous systems are deeply attuned to the energy of those around us, creating a ripple effect that transcends words or actions. This phenomenon—sometimes called social resonance—is why we instinctively calm down when in the presence of someone grounded or feel a surge of stress when surrounded by tension.

In forests, when a tree is injured, its neighbours—regardless of species—send nutrients and chemical signals through the mycelium to aid its recovery. This act of selfless care ensures the survival of the entire ecosystem. Similarly, in human communities, our internal ecosystems often rise to meet the needs of others. Acts of empathy—like comforting someone who is grieving or lending energy to a loved one in distress—are not just abstract gestures. They are tangible expressions of shared vitality, as our nervous systems synchronise and offer support.

The beauty of this connection is that it transcends individuality. Just as trees don’t distinguish between species when providing help, our bodies don’t need to "think" to respond empathetically. This transfer of energy and support happens naturally, reinforcing the truth that we are all part of a greater web of life.

These parallels remind us that our health and well-being are inseparable from the connections we maintain—with ourselves, with others, and with the natural world. When we care for our internal ecosystems—through mindful breath-work, for instance—we’re not just supporting our own health. We’re fortifying the energy we bring into the world, rippling that balance and calm outward.

5. Implications for Health and Nature

This analogy isn’t just poetic—it’s deeply practical. Understanding these connections can shift the way we view health and the environment.

In our bodies, when one part of the system becomes strained—such as shallow breathing or chronic stress—the entire network feels the impact. Practicing mindful breathwork, for example, not only nourishes the lungs but also calms the nervous system, much like replenishing a forest’s soil strengthens its trees.

Similarly, in nature, when we disrupt ecosystems by cutting down trees or polluting the soil, we sever the connections that sustain life. Protecting forests is not just an environmental issue; it’s a reflection of the care we need to give to all interconnected systems, including our own.

For those of us working with pelvic floor dysfunction or other physical imbalances, the lesson is clear: healing begins with restoring connection. Practices like Hypopressives tap into the relationship between breath, pressure, and alignment, much like nurturing soil restores the mycelium’s health.

6. Conclusion

The next time you step outside, take a moment to observe the trees around you. Picture their roots stretching deep into the earth, supported by a vast fungal network that remains unseen yet vital. Then, turn your attention inward—to your breath and the steady pulse of your nervous system. These are not separate worlds; they mirror each other, teaching us that life thrives on connection, balance, and care.

When we honour these parallels, we deepen not only our understanding of health but also our bond with the planet. After all, we are not apart from nature—we are a part of it.

If you would like to dive deeper into the holistic pelvic floor work I coach that ties in breath, posture, the nervous system and strength training (when you are ready). Then click HERE

Did you know this: The tracheobronchial tree is where air passes to your lungs and exchanges gases (oxygen and carbon dioxide). We even have tree as part of our anatomy …. x